Knight at the Movies Archives

Writer Michael Cunningham re-imagines Susan Minot's character stuffed novel with mixed results, Michael Moore returns with

another ripe winner

another ripe winner

In addition to being a writer I am also a musician and sometime band leader. For years one of my bands was highly popular with

the North Shore WASP money crowd and played dozens of country club and private estate parties. The backing vocalist and myself,

both gay males, never failed to get hit on by at least one of the party attendees and usually several. We knew without being told

that these elderly gentlemen, clustered together apart from their wives and grown children checking us out, were closeted gays who

had opted for money and position rather than fealty to their true natures. We often wondered about the early lives of these men

and in director Lajos Koltai’s new movie Evening we have a character and circumstances that address this sad dilemma. That is

just the subplot of Evening a movie so rich with amazing actors and melancholy that in a summer of loud and increasingly razor thin

blockbusters feels like a breath of, well if not fresh air, at least something more substantial and intriguing: something with a bit of

substance to mull over after the credits roll.

Upstairs in a darkened room Vanessa Redgrave as Ann Grant Lord is dying. She’s in and out of the dream state that sometimes

accompanies the last stages – a state that will be very familiar to gay men who have witnessed too many loved ones die from AIDS.

In and out of consciousness, Ann is attended by her hospice caregiver (Eileen Atkins) and her two grown daughters Nina (Toni

Collette) and Constance (Natasha Richardson, Redgrave’s real life daughter). Nina, still trying to get her life together, represents

creativity and independence while Constance with the husband, kids and beautiful home represents homespun, sentimental values.

While the two sisters fuss a bit at each other their mother is dreaming of a pivotal weekend in her life from 50 years before: the

Newport wedding of her college friend Lila (played as a blushing, confused bride by Mamie Gummer and as older and resigned to her

fate by Gummer’s real life mother Meryl Streep).

Ann in a delirium state has mentioned that both she and Buddy (Hugh Dancy) loved Harris (Patrick Wilson) and that she and Harris

“killed” Buddy. This sets up the story, the majority of it told through the prism of Ann’s memory of what happened the fateful

weekend of Lila’s wedding. Buddy, Lila’s brother, it soon becomes apparent, is desperate that his touchstones – Lila, Ann and Harris

– not leave him and go on with their lives. Buddy and Lila are the children of the rigid Witterborn’s (Glenn Close, Barry Bostwick) who

obviously have had a hard time with Buddy’s desire to be a poet and much else – namely his unspoken homosexuality. Both Buddy

(who drinks to try and quash his sorrow) and Lila have unrequited crushes on Harris, the son of their housekeeper who grew up with

them but has now become a doctor. While these two fret over this easy going dreamboat (Buddy covertly, Lila overtly), Harris makes

a play for the decidedly bohemian Ann (played in her younger version by a winning Claire Danes) who can’t help but return the

ardor. When Ann gets up to sing a timorous version of “Time After Time” at the reception for Lila, it is Harris’ sultry, impromptu

harmonizing that saves the day and clinches the deal for Ann. During this long, impossibly beautiful starlit night, romance and

tragedy will come into play affecting the outcome of everyone involved.

That’s a lot of plot (and there’s more) for one movie to handle and Michael Cunningham, the writer of “The Hours” and “A Home at

the End of the World” who also happens to be gay, hasn’t quite successfully pulled off his adaptation of Susan Minot’s sprawling

novel (adapted along with Minot). But Koltai’s elegant, painterly cinematography – contrasting the stuffy interiors and glorious

exteriors – give this story of regret, acceptance, missed opportunities, and what is passed on or withheld to the next generation a

gorgeous canvas upon which to play out the story that helps it enormously. There are lyrical moments – Vanessa Redgrave chasing

the elusive butterfly of love, Claire Danes in a sailboat at sunset gazing toward Redgrave on shore in a flowing black cocktail dress,

Hugh Dancy’s face bathed in moonlight as he entreats Ann to share a life with him because she will “understand” – that help one

overlook the feeling that for all the talent and lush production design put forth, something about the movie doesn’t quite land. Why

doesn’t it? Too many plot strands? The mixed signals the characters keep throwing off? The movie’s insistence on neatly wrapping

things up? The abundance of weighty sentimentality, an awkward cross between The Bridges of Madison County and The Way We Were

perhaps?

But the “something’s not quite right here” rumblings one feels wash away when the movie arrives at the scene it’s been building

toward: the death bed reunion of Ann and the now grown Lila. This meeting of Redgrave and Streep, those two acting titans, is brief

but electrifying. Even without them Evening is this season’s The Notebook or The Lake House – the reach for the tissue, tragic romance

drama lovey-dovey couples and moonstruck gay men have been craving. With them, it’s surely got the greatest special effect any

movie will offer this summer.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

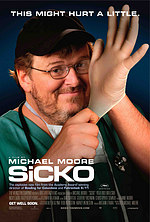

Michael Moore’s ability to get audiences to focus on serious social ills and do so while putting on not just a happy face but while

laughing, has never worked quite so well as it does with Sicko. The movie, a true cautionary tale if there ever was one, zeros in on

the shameful state of health care in America, a country that used to pride itself on taking care of its own. Instead of focusing on

America’s uninsured as expected the activist filmmaker presents examples of how the corporate mentality that has taken over the

insurance industry is having tragic consequences on regular folks WITH insurance. It’s an ironic distinction but one that’s not won’t

surprise many in the gay community used to insurance company chicanery after decades of claim denials for those suffering from

HIV and AIDS.

Moore uses his patented techniques – presenting the most horrific, sardonic stories (a man having to decide between which fingertip

to keep based on how much it will cost, a young woman being denied coverage for a trip to the hospital in an ambulance because

she didn’t get it pre-approved before becoming unconscious, etc.) placed against impossibly perky Muzak selections to help

underscore his points. As usual he helps the audience retain the seriousness of his subject by dosing them with spoonfuls of sugar,

laughs and pathos to help the medicine go down (almost literally this time out).

Unlike previous efforts, Sicko dispenses with most of Moore’s patented political propaganda for a more humanistic approach. Or

does he? In tone, the movie doesn’t seem all that different from Roger & Me, Bowling for Columbine or Fahrenheit 9/11. He’s just

working with a subject matter that touches everyone in this country without distinction. Sicko makes you sick with the injustices that

we’ve allowed to go on in the name of corporate profit and leaves you with a desire to either fix up the mess we’re in or move

immediately to Canada, England, France, or Cuba – where the many examples of the everyday miracles of socialized medicine

presented in the movie almost seem like a fairy tale.

the North Shore WASP money crowd and played dozens of country club and private estate parties. The backing vocalist and myself,

both gay males, never failed to get hit on by at least one of the party attendees and usually several. We knew without being told

that these elderly gentlemen, clustered together apart from their wives and grown children checking us out, were closeted gays who

had opted for money and position rather than fealty to their true natures. We often wondered about the early lives of these men

and in director Lajos Koltai’s new movie Evening we have a character and circumstances that address this sad dilemma. That is

just the subplot of Evening a movie so rich with amazing actors and melancholy that in a summer of loud and increasingly razor thin

blockbusters feels like a breath of, well if not fresh air, at least something more substantial and intriguing: something with a bit of

substance to mull over after the credits roll.

Upstairs in a darkened room Vanessa Redgrave as Ann Grant Lord is dying. She’s in and out of the dream state that sometimes

accompanies the last stages – a state that will be very familiar to gay men who have witnessed too many loved ones die from AIDS.

In and out of consciousness, Ann is attended by her hospice caregiver (Eileen Atkins) and her two grown daughters Nina (Toni

Collette) and Constance (Natasha Richardson, Redgrave’s real life daughter). Nina, still trying to get her life together, represents

creativity and independence while Constance with the husband, kids and beautiful home represents homespun, sentimental values.

While the two sisters fuss a bit at each other their mother is dreaming of a pivotal weekend in her life from 50 years before: the

Newport wedding of her college friend Lila (played as a blushing, confused bride by Mamie Gummer and as older and resigned to her

fate by Gummer’s real life mother Meryl Streep).

Ann in a delirium state has mentioned that both she and Buddy (Hugh Dancy) loved Harris (Patrick Wilson) and that she and Harris

“killed” Buddy. This sets up the story, the majority of it told through the prism of Ann’s memory of what happened the fateful

weekend of Lila’s wedding. Buddy, Lila’s brother, it soon becomes apparent, is desperate that his touchstones – Lila, Ann and Harris

– not leave him and go on with their lives. Buddy and Lila are the children of the rigid Witterborn’s (Glenn Close, Barry Bostwick) who

obviously have had a hard time with Buddy’s desire to be a poet and much else – namely his unspoken homosexuality. Both Buddy

(who drinks to try and quash his sorrow) and Lila have unrequited crushes on Harris, the son of their housekeeper who grew up with

them but has now become a doctor. While these two fret over this easy going dreamboat (Buddy covertly, Lila overtly), Harris makes

a play for the decidedly bohemian Ann (played in her younger version by a winning Claire Danes) who can’t help but return the

ardor. When Ann gets up to sing a timorous version of “Time After Time” at the reception for Lila, it is Harris’ sultry, impromptu

harmonizing that saves the day and clinches the deal for Ann. During this long, impossibly beautiful starlit night, romance and

tragedy will come into play affecting the outcome of everyone involved.

That’s a lot of plot (and there’s more) for one movie to handle and Michael Cunningham, the writer of “The Hours” and “A Home at

the End of the World” who also happens to be gay, hasn’t quite successfully pulled off his adaptation of Susan Minot’s sprawling

novel (adapted along with Minot). But Koltai’s elegant, painterly cinematography – contrasting the stuffy interiors and glorious

exteriors – give this story of regret, acceptance, missed opportunities, and what is passed on or withheld to the next generation a

gorgeous canvas upon which to play out the story that helps it enormously. There are lyrical moments – Vanessa Redgrave chasing

the elusive butterfly of love, Claire Danes in a sailboat at sunset gazing toward Redgrave on shore in a flowing black cocktail dress,

Hugh Dancy’s face bathed in moonlight as he entreats Ann to share a life with him because she will “understand” – that help one

overlook the feeling that for all the talent and lush production design put forth, something about the movie doesn’t quite land. Why

doesn’t it? Too many plot strands? The mixed signals the characters keep throwing off? The movie’s insistence on neatly wrapping

things up? The abundance of weighty sentimentality, an awkward cross between The Bridges of Madison County and The Way We Were

perhaps?

But the “something’s not quite right here” rumblings one feels wash away when the movie arrives at the scene it’s been building

toward: the death bed reunion of Ann and the now grown Lila. This meeting of Redgrave and Streep, those two acting titans, is brief

but electrifying. Even without them Evening is this season’s The Notebook or The Lake House – the reach for the tissue, tragic romance

drama lovey-dovey couples and moonstruck gay men have been craving. With them, it’s surely got the greatest special effect any

movie will offer this summer.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Michael Moore’s ability to get audiences to focus on serious social ills and do so while putting on not just a happy face but while

laughing, has never worked quite so well as it does with Sicko. The movie, a true cautionary tale if there ever was one, zeros in on

the shameful state of health care in America, a country that used to pride itself on taking care of its own. Instead of focusing on

America’s uninsured as expected the activist filmmaker presents examples of how the corporate mentality that has taken over the

insurance industry is having tragic consequences on regular folks WITH insurance. It’s an ironic distinction but one that’s not won’t

surprise many in the gay community used to insurance company chicanery after decades of claim denials for those suffering from

HIV and AIDS.

Moore uses his patented techniques – presenting the most horrific, sardonic stories (a man having to decide between which fingertip

to keep based on how much it will cost, a young woman being denied coverage for a trip to the hospital in an ambulance because

she didn’t get it pre-approved before becoming unconscious, etc.) placed against impossibly perky Muzak selections to help

underscore his points. As usual he helps the audience retain the seriousness of his subject by dosing them with spoonfuls of sugar,

laughs and pathos to help the medicine go down (almost literally this time out).

Unlike previous efforts, Sicko dispenses with most of Moore’s patented political propaganda for a more humanistic approach. Or

does he? In tone, the movie doesn’t seem all that different from Roger & Me, Bowling for Columbine or Fahrenheit 9/11. He’s just

working with a subject matter that touches everyone in this country without distinction. Sicko makes you sick with the injustices that

we’ve allowed to go on in the name of corporate profit and leaves you with a desire to either fix up the mess we’re in or move

immediately to Canada, England, France, or Cuba – where the many examples of the everyday miracles of socialized medicine

presented in the movie almost seem like a fairy tale.

Then and Now:

Evening-Sicko

Expanded Edition of 6-20-07 Windy City Times Knight at the Movies Column

By Richard Knight, Jr.

Evening-Sicko

Expanded Edition of 6-20-07 Windy City Times Knight at the Movies Column

By Richard Knight, Jr.