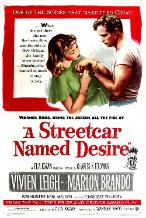

The Brando Effect is still intact 59 years after the premiere of A Streetcar Named Desire

film from a queer perspective

Essay

| KATM media outlets |

| KATM featured weekly |

| Join Us! |

| KATM on RT |

| Vidcast Starring KATM |

| NOTE: THIS SITE ONLY LOADS CORRECTLY WITH EXPLORER AND MOZILLA BROWSERS - SORRY SAFARI USERS! |

| Buy the KATM Book |

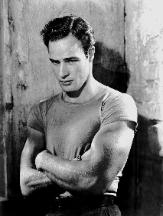

Marlon Lives On:

The Brando Effect

1-27-10 Windy City Times Column

By Richard Knight, Jr.

The Brando Effect

1-27-10 Windy City Times Column

By Richard Knight, Jr.

| It doesn’t take much of a stretch of the imagination to point out that gays objectified men on the screen decades before Marlon Brando’s riveting screen performance as the brutish über hunk Stanley Kowalski in Elia Kazan’s 1951 masterpiece A Streetcar Named Desire. Tyrone Power, Robert Taylor, Cary Grant, Gary Cooper, Joel McCrea, Montgomery Clift, and Clark Gable’s removal of his undershirt in 1934’s It Happened One Night all preceded Brando’s real arrival at the movies in Streetcar (he had been seen by audiences as the bitter paraplegic in 1950’s The Man before this). But the combination of Brando’s frank portrayal of the heated Stanley, his blasé attitude about applying sexual labels in real life, his insistence in interviews about discussing acting as an art and not just as a means to a paycheck, his derision about stardom and the limits it enforced on those who accepted its constraints, and more than anything, his overripe beauty and physicality all said to canny moviegoers encountering him on the screen in Streetcar, straight and gay, “Go ahead – let your imagination run wild.” Here at last was an actor who knew he turned on both women and men and didn’t give a damn. Whose objectification in fact, may have turned him on, to. Almost 59 years after Streetcar’s initial release Brando’s sexual potency hasn’t dimmed a whit. Kazan, who had directed the groundbreaking 1947 Broadway production of the Tennessee Williams play had already conquered Hollywood and had to be coaxed into returning to Streetcar and directing it for the screen. Part of the reason he made the film was a chance to balance the movie version more judiciously between Blanche and Stanley – a decision that actually turns up the heat. Kazan first gives us a look at Stanley through the star struck eyes of Blanche’s sister Stella (Kim Hunter). Finding her younger sister and husband in a bowling alley, Blanche (Vivien Leigh), the delicate, wilted Southern belle recoils when Stella points out roughneck Stanley who is briefly glimpsed in the midst of a scuffle with a group of men. Back at the cramped apartment of Stella and Stanley, Kazan’s camera lingers on Brando who does a subconscious striptease for Blanche in his first meeting with her. Stella has retreated to the bathroom to escape Blanche’s unexpected recriminations and when Stanley strides into the apartment, she’s shy and reserved. Stanley quickly removes first his silk bowling jacket and then his sweat stained t-shirt. Nonchalantly, he takes his time about putting on a fresh t-shirt as Blanche gapes open mouthed, almost salivating (standing in for the audience, unaccustomed to having their baser instincts so precisely laid open). Interesting trivia: Brando’s chest was shaved and his skintight t-shirts were custom made to cling to the contours of his muscular torso. This outright objectification is part of the genius of Williams’ Streetcar – despite Stanley’s crude tirades and his tendency toward emotional and physical violence his sexual hold on Stella and eventually Blanche trumps everything (both women at various moments act as stand-ins for the audience, equally enthralled). In Today’s enlightened, sexed up age we quickly intuit Stella (and the audience) as being “dickmatized” by Stanley. But in 1951 Williams’ lyrical writing provided the subtext for what was then an unexplored “fact of life” (and I’ve always loved that it took a gay playwright to bring this unacknowledged human behavior to the mainstream). Brando’s performance, as the film attests, made this possible – as it still does. No other male star of the era could have given the role the unforgettable, unignorable magnetic power it retains. A Streetcar Named Desire ushered in a decade of both sexually tinged melodramas and the era of movie stars as sexual glamazons – the physically imposing Rock Hudson, Tab Hunter, and the rest of their ilk for the men and Marilyn Monroe and her thousand imitators for the women (it’s also ironic to note the prominence of these in your face sexual movie stars during the 1950s – the decade of conservative repression). Brando enjoyed many other “firsts” when it came to his appearance in movies but his opening the floodgates for outright sexual objectification (Monroe did it for women) for film audiences of all stripes may be his true legacy – certainly it’s his most potent. And objectification is surely one of the most primal allures of the medium – conscious or not. Brando’s sexual influence and his rebellious attitude on American society (not to mention gay culture with the experimental films of Kenneth Anger as just one prime example of the Brando Effect) is almost incalculable and it all started with the removal of that sweaty t-shirt. With regard to movies, as director Martin Scorsese has noted, “There’s before Brando and after Brando.” Film audiences who haven’t experienced Streetcar on the big screen and The Brando Effect will have the chance to see the movie on Jan. 30 at 3pm and Feb. 1st at 6pm at the Gene Siskel Film Center (164 N. State Street). The film – which is a glorious, mesmerizing experience from beginning to end (Brando’s performance is matched by Leigh’s and the supporting cast of Hunter, Karl Malden et al – all speaking Williams lyrical dialogue, set to Alex North’s hot jazz score) – is being shown as part of the Siskel’s month long tribute to Kazan. Titled “Elia Kazan’s American Century,” the series has included the majority of the late director’s masterworks. 1956’s highly erotic Baby Doll, Kazan’s second collaboration with Tennessee Williams, which introduced audiences to actress Carroll Baker and to another daring Williams’ sexually tinged taboo – is on the bill for Jan. 28th at 6pm. www.siskelfilmcenter.org More Classic Cinema: Beginning on Jan. 29 the Music Box Theatre is presenting a double feature of Sir Carol Reed’s 1947 British suspense thrillers Odd Man Out starring James Mason and 1949’s The Third Man starring Joseph Cotton and Orson Welles (it features perhaps one of filmdom’s most memorable music scores). The former will feature a new 35mm print. www.musicboxtheatre.com |