Knight at the Movies Archives

Tom Ford makes a stunning feature debut, Rob Marshall tries another musical and Mr. O'Day returns for a second capsizing

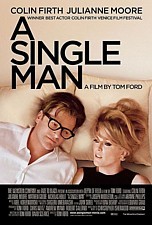

The ghost of Alfred Hitchcock hangs heavy over Tom Ford’s sensational debut feature A Single Man. Like the late director’s chilly

masterpiece Vertigo, the obsessive detail of the off camera direction is reflected in every movement of the characters onscreen. It’s

a visually stunning film in which the viewer is aware at every moment that they are watching a movie unfold as willed by the director.

Not one single element of this sensationally moving drama has been left untouched by Ford and it’s his exceeding good fortune that

the material matches his talents so precisely. Like Charles Laughton, the deeply closeted director of the deeply closeted queer

classic Night of the Hunter, Ford, who directed, co-wrote, produced, and personally financed A Single Man after walking away from his

contract as clothing designer for Gucci, might want to stop at the one picture leaving an unsullied reputation intact. That’s how

perfectly composed and assured a movie it is.

The film, based on the 1964 novel by author and gay icon Christopher Isherwood, takes place on a single day and night in

November of 1962 during the Cuban missile crisis (a particularly fertile moment for authors and filmmakers). George Falconer (Colin

Firth, outshining even his usual excellent work), a college English professor, is still in the throes of bereavement eight months after

the death of Jim, his partner of 14 years who was killed in a car accident (along with one of their dogs) while visiting his family in

Colorado.

Jim (played by Matthew Goode who makes wonderful use of his brief screen time) was an architect who designed the modern house

of glass, wood and stone the two shared. We learn in voice over that George has decided that this day will be different. No more

going through the motions – waking from the never ending nightmare of seeing Jim lying by the car in the snow, his lips

unresponsive to George’s warm kiss. No more endless perfect California sunshine days of picking out just the right accessories and

clothes, the annoyance of the neighbor children, the disinterested college students, the routine of work and alcohol soaked

encounters with Charley, the boozy glamour gal pal and one time lover (Julianne Moore playing with typical finesse), or the

unbearably haunted memories of a rich full life with Jim. George has decided to end the pain by killing himself.

But even as we see George making his elaborate preparations his plans are put awry thanks to an assortment of interruptions as the

day turns into night. There’s George’s bewitching fellow London expat Charley who won’t stop phoning up to remind him about

dinner that night, the neighborhood child (a doppelganger for The Bad Seed’s Rhoda Morgenstern with her shocking blue pinafore and

blonde pigtails) who seems to have preternatural insight into his situation, the child’s mother who obviously senses his grief. A

hunky hustler named Carlos (John Kortajarena) distracts him with a proposition outside a liquor store. Finally, there’s the

breathtakingly beautiful Kenny (Nicholas Hoult, who makes for one hell of a fetching protégé), with his tight white jeans and angora

sweater (a subconscious nod to Ed Wood’s transvestite classic Glen Or Glenda?) who keeps challenging him with provocative

comments and barely concealed lust (he uses the word “sir” while gazing into George’s eyes at least 40 times).

So George, who is photographed in color leeched tones of gray, black, brown and white, keeps getting sidetracked from his mission

and his aching memories of life with Jim. As a contrast, Ford has his cinematographer Eduard Grau shoot the flashbacks and the

characters that connect with George’s conscious in saturated, over the top color – an effective, artificial device that emphasizes

George’s emotional isolation. This device will irritate some with its redundancy (though I dug it) as will Ford’s decision to use the

camera to eroticize everything that George sees – clocks, cars, ashtrays, hairdos, furniture, shirtless college boys playing tennis, and

of course the clothes are fetish totems almost to the point of distraction. The sets are a dream of early 60s luxe taste (designed by

Amy Welles), too. It’s as if an aesthete had directed an episode of “Mad Men” without concern for the budget (and when a voice on

the phone calls up to tell George about Jim’s death – a heartbreaking scene – it makes perfect sense that it’s the voice of “Mad

Men” leading actor Jon Hamm on the other end of the line).

On first viewing the stunning cinematography (even when we see Firth on the toilet it’s awfully pretty), gorgeous music score (the

year’s best by Abel Korzeniowski, referencing Hitchcock’s collaborator Bernard Herrmann), exquisite production design (by Dan

Bishop) and Ford’s precision and his innate gay sensibility (George’s memories of Jim and his encounters with Kenny are like a

prolonged, achingly erotic wet dream) might obscure the enormously complex performances of Firth and Moore so I recommend a

second and perhaps a third viewing of A Single Man – once to revel in the carefully crafted artifice, the second time to fully appreciate

the complex performances and the third to luxuriate in Ford’s singular achievement. A Single Man is not just the best queer themed

movie of the year – it’s one of the best. Period.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

It’s the week of the queer director movies. From Tom Ford we move to Rob Marshall, Oscar winner for Chicago who had a misstep

with Memoirs of a Geisha and now has another with Nine, the long awaited big screen version of the Broadway musical, in turn based

on Fellini’s 8 ½.

The material focuses on the fictional Guido Contini (played by Daniel Day-Lewis), the brilliant God of Italian cinema (Fellini’s alter

ego) who is having a career crisis. It’s 1965 and La Dolce Vita, Italian style is in full swing – the gorgeous women and men, the

snazzy fashions and sports cars, the swinging nightlife scene – but Contini is having none of it. He is surrounded (and hounded) by

the insistent, ever present women in his life – from his acerbic costume designer (Judi Dench in a clipped page boy), his wife, the

patient, loving Luisa (a wonderfully emotive Marion Cotillard), his chatterbox of a mistress (the sensational beauty Penelope Cruz), a

persistent journalist (Kate Hudson doing a fun imitation of her mother Goldie circa her “Laugh In” days), a touchy movie star (Nicole

Kidman who registers well in her one number), and the memories of women past – especially from his late mother (the legendary

Sophia Loren who apparently does not age) and Saraghina the whore on the beach, his first sexual encounter (Fergie belting out the

signature “Be Italian”). Guidi can’t come up with an idea – let alone a script – for his next picture and as he roams through a tour of

his life each of the ladies sings to him, about him, for him. None of it and all of it seems to move him, this creative enigma at the

center of their lives.

Onstage, Maury Yeston’s sophisticated though mostly unhummable score matched to the acrid ennui of Fellini’s original story was

aided by the immediacy of live theatre (and in the revival, the electrifying performance of Antonio Banderas in the leading part). But

onscreen, stripped of Fellini’s genius behind the camera the material is shockingly thin and repetitious (at least three of the women

characters sing a ballad and then cry for their Guido at the end of it for example). It’s essentially a revue and Marshall, who sets

much of the action on a barren soundstage, attempts to liven things up by choreographing like mad and dazzling camera work (this

works perfectly for “Cinema Italiano,” the new song Yeston composed for the film performed by Hudson and Fergie’s “Be Italian,” a

direct homage to “Mein Herr” from Cabaret but less so for the Dench solo and the truncated opening number).

All very entertaining but it’s not until Cotillard sings the one real scorcher in the score – “My Husband Makes Movies” – that the film

emotionally takes hold. That it doesn’t stay there, I think, has a lot to do with a problem that no amount of creativity on Marshall’s

part and his technicians (and there is much in evidence here – the fashions and the wigs are particularly fetching) could have

overcome. That is the absolute miscasting of Daniel Day-Lewis in the title role.

Day-Lewis speaks and sings (in a light tenor) in a perfectly sculpted Italian accent but though Marshall could get away with filming

Chicago in Toronto he can’t disguise that Day-Lewis is neither Italian nor an effortless chick magnet – essential requirements for the

role. He just looks wrong. There is nothing in the actor’s angular physicality that is irresistibly sensual and one never sees the

impish little boy, the twinkle in his eye (and it’s impossible to believe that the little Guido we see will ever grow up to be this scruffy

chain smoking worry wart). Day-Lewis acts the role admirably and it isn’t his fault that he isn’t physically right for the part but with a

character so integral to the piece, the miscasting throws the entire movie off kilter and one is left to contemplate the holes in the

material.

“I would see Rome the way you interpret it in your movies,” Loren tells Day-Lewis at one point. If Marshall had gone against the

money men and insisted on Banderas (who apparently wasn’t used because he wasn’t considered box office) or if he’d waited for

Javier Bardem to return to the role (or even tried a newcomer like Giles Marini, the Sex & the City/Dancing with the Stars hottie as a

friend suggested) that might have been the case and Nine might be getting a Ten from this reviewer. Instead of a Six.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Department of Shameless Self Promotion AGAIN: Attention land lubbers! In a nice alternative to the bars this New Year’s Eve my

alter ego Dick O’Day is hosting another edition of Camp Midnight, the film series dedicated to presenting “the best of the worst.” Im

once again teaming up with David Cerda and his crew of Handbag Production players and the Music Box for a New Year’s Eve

screening of the 1972 disaster flick The Poseidon Adventure. At The Upside Down New Year's Eve Adventure we’ll have a jam

packed pre-show, complete with contests, surprise performances, prizes and more beginning at 11pm followed by the screening.

And get this: when the ship flips onscreen at Midnight as Shelley Winters, Stella Stevens, Ernest Borgnine et al are celebrating their

fateful New Year’s Eve aboard the S.S. Poseidon we’ll be doing the exact same thing in the theatre. Tickets, which include a

champagne toast and party favors, an audience interactive screening guide and more are $20 in advance, $25 at the door. Last

year's was a hoot! Don't miss out! www.musicboxtheatre.com

masterpiece Vertigo, the obsessive detail of the off camera direction is reflected in every movement of the characters onscreen. It’s

a visually stunning film in which the viewer is aware at every moment that they are watching a movie unfold as willed by the director.

Not one single element of this sensationally moving drama has been left untouched by Ford and it’s his exceeding good fortune that

the material matches his talents so precisely. Like Charles Laughton, the deeply closeted director of the deeply closeted queer

classic Night of the Hunter, Ford, who directed, co-wrote, produced, and personally financed A Single Man after walking away from his

contract as clothing designer for Gucci, might want to stop at the one picture leaving an unsullied reputation intact. That’s how

perfectly composed and assured a movie it is.

The film, based on the 1964 novel by author and gay icon Christopher Isherwood, takes place on a single day and night in

November of 1962 during the Cuban missile crisis (a particularly fertile moment for authors and filmmakers). George Falconer (Colin

Firth, outshining even his usual excellent work), a college English professor, is still in the throes of bereavement eight months after

the death of Jim, his partner of 14 years who was killed in a car accident (along with one of their dogs) while visiting his family in

Colorado.

Jim (played by Matthew Goode who makes wonderful use of his brief screen time) was an architect who designed the modern house

of glass, wood and stone the two shared. We learn in voice over that George has decided that this day will be different. No more

going through the motions – waking from the never ending nightmare of seeing Jim lying by the car in the snow, his lips

unresponsive to George’s warm kiss. No more endless perfect California sunshine days of picking out just the right accessories and

clothes, the annoyance of the neighbor children, the disinterested college students, the routine of work and alcohol soaked

encounters with Charley, the boozy glamour gal pal and one time lover (Julianne Moore playing with typical finesse), or the

unbearably haunted memories of a rich full life with Jim. George has decided to end the pain by killing himself.

But even as we see George making his elaborate preparations his plans are put awry thanks to an assortment of interruptions as the

day turns into night. There’s George’s bewitching fellow London expat Charley who won’t stop phoning up to remind him about

dinner that night, the neighborhood child (a doppelganger for The Bad Seed’s Rhoda Morgenstern with her shocking blue pinafore and

blonde pigtails) who seems to have preternatural insight into his situation, the child’s mother who obviously senses his grief. A

hunky hustler named Carlos (John Kortajarena) distracts him with a proposition outside a liquor store. Finally, there’s the

breathtakingly beautiful Kenny (Nicholas Hoult, who makes for one hell of a fetching protégé), with his tight white jeans and angora

sweater (a subconscious nod to Ed Wood’s transvestite classic Glen Or Glenda?) who keeps challenging him with provocative

comments and barely concealed lust (he uses the word “sir” while gazing into George’s eyes at least 40 times).

So George, who is photographed in color leeched tones of gray, black, brown and white, keeps getting sidetracked from his mission

and his aching memories of life with Jim. As a contrast, Ford has his cinematographer Eduard Grau shoot the flashbacks and the

characters that connect with George’s conscious in saturated, over the top color – an effective, artificial device that emphasizes

George’s emotional isolation. This device will irritate some with its redundancy (though I dug it) as will Ford’s decision to use the

camera to eroticize everything that George sees – clocks, cars, ashtrays, hairdos, furniture, shirtless college boys playing tennis, and

of course the clothes are fetish totems almost to the point of distraction. The sets are a dream of early 60s luxe taste (designed by

Amy Welles), too. It’s as if an aesthete had directed an episode of “Mad Men” without concern for the budget (and when a voice on

the phone calls up to tell George about Jim’s death – a heartbreaking scene – it makes perfect sense that it’s the voice of “Mad

Men” leading actor Jon Hamm on the other end of the line).

On first viewing the stunning cinematography (even when we see Firth on the toilet it’s awfully pretty), gorgeous music score (the

year’s best by Abel Korzeniowski, referencing Hitchcock’s collaborator Bernard Herrmann), exquisite production design (by Dan

Bishop) and Ford’s precision and his innate gay sensibility (George’s memories of Jim and his encounters with Kenny are like a

prolonged, achingly erotic wet dream) might obscure the enormously complex performances of Firth and Moore so I recommend a

second and perhaps a third viewing of A Single Man – once to revel in the carefully crafted artifice, the second time to fully appreciate

the complex performances and the third to luxuriate in Ford’s singular achievement. A Single Man is not just the best queer themed

movie of the year – it’s one of the best. Period.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

It’s the week of the queer director movies. From Tom Ford we move to Rob Marshall, Oscar winner for Chicago who had a misstep

with Memoirs of a Geisha and now has another with Nine, the long awaited big screen version of the Broadway musical, in turn based

on Fellini’s 8 ½.

The material focuses on the fictional Guido Contini (played by Daniel Day-Lewis), the brilliant God of Italian cinema (Fellini’s alter

ego) who is having a career crisis. It’s 1965 and La Dolce Vita, Italian style is in full swing – the gorgeous women and men, the

snazzy fashions and sports cars, the swinging nightlife scene – but Contini is having none of it. He is surrounded (and hounded) by

the insistent, ever present women in his life – from his acerbic costume designer (Judi Dench in a clipped page boy), his wife, the

patient, loving Luisa (a wonderfully emotive Marion Cotillard), his chatterbox of a mistress (the sensational beauty Penelope Cruz), a

persistent journalist (Kate Hudson doing a fun imitation of her mother Goldie circa her “Laugh In” days), a touchy movie star (Nicole

Kidman who registers well in her one number), and the memories of women past – especially from his late mother (the legendary

Sophia Loren who apparently does not age) and Saraghina the whore on the beach, his first sexual encounter (Fergie belting out the

signature “Be Italian”). Guidi can’t come up with an idea – let alone a script – for his next picture and as he roams through a tour of

his life each of the ladies sings to him, about him, for him. None of it and all of it seems to move him, this creative enigma at the

center of their lives.

Onstage, Maury Yeston’s sophisticated though mostly unhummable score matched to the acrid ennui of Fellini’s original story was

aided by the immediacy of live theatre (and in the revival, the electrifying performance of Antonio Banderas in the leading part). But

onscreen, stripped of Fellini’s genius behind the camera the material is shockingly thin and repetitious (at least three of the women

characters sing a ballad and then cry for their Guido at the end of it for example). It’s essentially a revue and Marshall, who sets

much of the action on a barren soundstage, attempts to liven things up by choreographing like mad and dazzling camera work (this

works perfectly for “Cinema Italiano,” the new song Yeston composed for the film performed by Hudson and Fergie’s “Be Italian,” a

direct homage to “Mein Herr” from Cabaret but less so for the Dench solo and the truncated opening number).

All very entertaining but it’s not until Cotillard sings the one real scorcher in the score – “My Husband Makes Movies” – that the film

emotionally takes hold. That it doesn’t stay there, I think, has a lot to do with a problem that no amount of creativity on Marshall’s

part and his technicians (and there is much in evidence here – the fashions and the wigs are particularly fetching) could have

overcome. That is the absolute miscasting of Daniel Day-Lewis in the title role.

Day-Lewis speaks and sings (in a light tenor) in a perfectly sculpted Italian accent but though Marshall could get away with filming

Chicago in Toronto he can’t disguise that Day-Lewis is neither Italian nor an effortless chick magnet – essential requirements for the

role. He just looks wrong. There is nothing in the actor’s angular physicality that is irresistibly sensual and one never sees the

impish little boy, the twinkle in his eye (and it’s impossible to believe that the little Guido we see will ever grow up to be this scruffy

chain smoking worry wart). Day-Lewis acts the role admirably and it isn’t his fault that he isn’t physically right for the part but with a

character so integral to the piece, the miscasting throws the entire movie off kilter and one is left to contemplate the holes in the

material.

“I would see Rome the way you interpret it in your movies,” Loren tells Day-Lewis at one point. If Marshall had gone against the

money men and insisted on Banderas (who apparently wasn’t used because he wasn’t considered box office) or if he’d waited for

Javier Bardem to return to the role (or even tried a newcomer like Giles Marini, the Sex & the City/Dancing with the Stars hottie as a

friend suggested) that might have been the case and Nine might be getting a Ten from this reviewer. Instead of a Six.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Department of Shameless Self Promotion AGAIN: Attention land lubbers! In a nice alternative to the bars this New Year’s Eve my

alter ego Dick O’Day is hosting another edition of Camp Midnight, the film series dedicated to presenting “the best of the worst.” Im

once again teaming up with David Cerda and his crew of Handbag Production players and the Music Box for a New Year’s Eve

screening of the 1972 disaster flick The Poseidon Adventure. At The Upside Down New Year's Eve Adventure we’ll have a jam

packed pre-show, complete with contests, surprise performances, prizes and more beginning at 11pm followed by the screening.

And get this: when the ship flips onscreen at Midnight as Shelley Winters, Stella Stevens, Ernest Borgnine et al are celebrating their

fateful New Year’s Eve aboard the S.S. Poseidon we’ll be doing the exact same thing in the theatre. Tickets, which include a

champagne toast and party favors, an audience interactive screening guide and more are $20 in advance, $25 at the door. Last

year's was a hoot! Don't miss out! www.musicboxtheatre.com

Tom, Rob and Dick:

A Single Man-Nine-Camp Midnight Presents The Poseidon Adventure

Expanded Edition of 12-23-09 Windy City Times Column

By Richard Knight, Jr.

A Single Man-Nine-Camp Midnight Presents The Poseidon Adventure

Expanded Edition of 12-23-09 Windy City Times Column

By Richard Knight, Jr.